Complete the look!

The Kilt is so ubiquitous

that it has it’s own pages:

• the history of the Kilt

• Wearing and choosing your kilt

Kilt Pins

The custom of wearing a pin came in during Queen Victoria's reign to stop the kilt apron flapping about and showing more anatomy than she liked. The story goes that the Queen gave her own brooch to a soldier who was struggling with his kilt in windy conditions.

Author J. Charles Thompson writes that Queen Victoria brought in rules stating that all military kilts must have a fastening, and although the soldiers then wore kilt pins, they didn't fasten the layers of cloth with them as that would change the way the kilt hung

For Highlanders, their dress provided them with an opportunity to display as much wealth as they could afford. Therefore, ornamentation, such as kilt pins, were very important.

Even those who were less well-off spent lavishly on these accessories which were ornate and had precious and semi-precious stones set in them. Money spent here was also for practical reasons as if a clansman died, the silver accessories on their dress would cover the cost of a decent burial.

Kilt pins come in different style and are appropriate for different occasions. The simplest style of pin is a large safety pin. This or a blanket pin is suggested for sports dress.

Whereas a more ornate pin would be appropriate for formal day wear, and a silver pin with a stone set in it would be expected for evening wear. In this way the kilt pin matches the formality of the dress and occasion.

The pin should be applied vertically (or on a slight angle) at the base of the kilt flap (approximately at the end of your fingertips, when standing).

Kilt Jackets

Prince Charlie Kilt Jacket

The Prince Charlie Jacket is a more formal and dressy choice that should be reserved for formal, evening events - comparable to the American tuxedo and is worn with a vest and a bowtie.

This jacket is usually worn in black or red and comes embellished with scalloping details as well as silver buttons. The front of the jacket is shorter with longer tails in the back. The tails are also decorated with silver buttons adding the formality of the Prince Charlie Jacket.

Other dressy accessories should accompany this jacket and, of course, this jacket is worn with a traditional kilt. Overall, this jacket is elegant and straightforward truly displaying the Scottish tradition and pride at its best.

Argyll Kilt Jacket

With less formality than the Prince Charlie Jacket, the more familiar Argyll Jacket illustrates its versatility in its use being appropriate for a wedding, Highland Games or even just a day wear.

Depending on the colour and material it is made of, this jacket can be worn with a shirt and tie for less formal events, or if it’s particularly dressy, it can be worn with a bow tie for more formal events.

This jacket is the same length all around falling to just below the waist.

This too comes with silver buttons on the front of the jacket, the sleeves of the jacket, and the back of the jacket.

It is made of either wool or tweed with lining on the inside.

It is common for these jackets to also have two pockets inside the jacket for storage of smaller objects.

What makes this jacket really stand out is its cuffs which include a variety of different options, including Argyle or the Crail Cuffs.

Tweed Kilt Jacket

A much more casual jacket is the Tweed Kilt Jacket which comes in a variety of neutral colours including grey, black and brown.

Fly plaid

The modern fly plaid is a homage to the grand kilt. The fly plaid replaced that portion of the Great Kilt that was draped over the shoulder. It is typically 1 to 1.4 metres square (39 to 54 inches) square, in the same tartan or colour as the kilt.

It is typically worn with a jacket that has epaulets (shoulder straps) but this is not mandatory, and fastened with a brooch. The fly plaid brooches have become a fashionable choice.

A plaid brooch is not only worn to keep the fly plaid in place, but it also allows you to show off your heritage above your heart.

It is only worn for formal ‘white tie' events such as by a groom on his wedding day. As such, if wearing a fly plaid to a highland event, one must request permission from the chief or chieftain of the event.

Badges and Broaches

It's said that clan chiefs would often give their clansmen a metal plate of their crest which could be worn as a sign of their allegiance. The usual method of fastening it to their clothing was with a leather belt and buckle and when it wasn't being worn, the belt was coiled around it.

Trews

Trews (Truis or Triubhas) are men's clothing for the legs and lower abdomen, a traditional form of tartan trousers. Trews could be trimmed with leather, usually buckskin, especially on the inner leg to prevent wear from riding on horseback.

They were always made of tartan and great ingenuity was used in their manufacture. They were cut on the bias - on the cross - so that they had a certain amount of elasticity and clung to the legs.

The sett of the tartan was usually smaller than seen on the kilt and the hose was carefully crafted to match on the seams which ran up the back of the leg on the outside - a little like the seams on old-fashioned ladies' nylon stockings.

Having no pockets, the wearer would often wear a sporran - usually hanging from the belt rather than on the front - and a plaid would also be worn.

In 1637 it was reported that "In the sharp winter weather the Highlandmen wear close trowzes which cover the thighs, legs and feet. To fence their feet they put on rullions or tan leather shoes."

The practicality of the trews became evident when riding a pony - not something that a kilt wearer would volunteer to do in a hurry - and since ponies and horses were usually the privilege of rank, trews came to be regarded as the domain of the rich.

Historian Frank Adam commented that they were worn principally by chiefs and gentlemen on horseback, and by Highlanders when travelling in the Lowlands.

Nowadays they've disappeared altogether (except possibly within re-enactment societies). Their successor in military circles are in effect very tight 'drainpipe' trousers.

Shirts

Scottish traditional Jacobite Ghillie Shirts, also called Jacobean shirts, are Highlander heritage shirts which worn with the Kilt.

Loose fit straight cut style Ghillie shirts come in a range of colours where the most popular are Off-white, white, Black and Navy Blue.

The Jacobite Ghillie shirt is characterised with leather lacing around the neck to fasten the chest.

There is no set rule to match or contrast the Ghillie shirt with your Tartan kilt outfit and is totally up to personal taste.

Hose

Most Highlanders went around bare-legged and bare-footed but when they did start wearing stockings, they were made of cloth and not knitted like modern ones.

The pattern was usually a red and white check which was called cath dath (pr: kaa dah) - war pattern.

A characteristic of traditional hose was that they stopped well below the knee - usually on the thickest part of the calf.

Even with garters however, those old diced hose were pretty shapeless and fell down frequently if the wearer didn't have a good-sized calf muscle and they were eventually replaced by knitted stockings which clung to the legs much better.

There is some evidence that Highlanders also wore footless hose as can be seen in the extract from a McIan painting of 1845

Garters / Flashers

There was no elastic in those days and to keep the socks up it's said that poorer Highlanders would often tie some plaited hay or straw around the top of them to hold them up.

For the better off however, garters were woven on a special hand loom called a gartane leem which was also used for weaving narrow strips of fabric.

Nowadays it's called an Inkle loom and was mentioned in Shakespeare's Love's Labour's Lost but the loom predated that period by several centuries.

The woven garters were about a metre long and ended in a special knot called the Sniomh Gartain (pr: snaime garshtan) which is said to be a bit like that on a modern necktie.

The village of Cladich on Loch Awe was said to be home to a colony of weavers - almost all of them MacIntyres- who were renowned for their hose and their 'greatly celebrated''Cladich garters' which were mostly made in red and white and were greatly prized by pipers.

Shoes

We know that Highlanders - men and women - frequently went barefooted in summer and winter, but when they wore shoes, they were what they called in Gaelic - brogan tionndaidh - made mostly from deerskin and pretty rough and ready. Martin Martin in 1703 wrote "The shoes antiently wore, were a piece of the hide of a deer, cow or horse, with the hair on, being tied behind and before with a point of leather."

To make them, the Highlander would lay his bit of deerskin on the ground - furry side down - place his foot on top and draw the material up around his foot, cut off the excess and then punch holes along the top of the instep through which he would thread deerskin thonging. He would then cut holes in each shoe to let the water out.

If he didn't do that, water would lie in the shoes and create what is known as footrot or 'trench foot' - a serious condition, which if unattended, could result in gangrene and amputation.

Captain Burt, an English engineering officer, was sent to Inverness in 1730 as a contractor and we owe much to his blunt and often ascerbic descriptions of life at that time:

“They are often barefoot, but some I have seen shod with a kind of pumps made out of a raw cow hide with the hair turned outward. They are not only offensive to the sight, but intolerable to the smell of those who are near them. By the way, they cut holes in their brogues though new made, to let out the water when they have far to go, and rivers to pass; this they do to prevent their feet from galling. (becoming sore). ”

Highlanders also wore a higher foot covering - a leather boot of untanned skin, which was laced up to just below the knee. These were called cuaran. Which now has become known as the brogue which has been fashionable for very many decades and which has, for decoration, a layer of punched holes on the uppers. Those early shoes were also the forerunners of modern Highland dress shoes -the ghillie brogues which utilise the same thonging method for lacing them up. as do the lightweight shoes used by Scottish Highland dancers.

It has been suggested that the word moccasin possibly had its roots in Scotland. The word comes from the American Indian mockasin and it was once recorded that Indians may have got it from early Scottish settlers speaking in Gaelic and referring to their shoes as mo chasan (my footwear). It seems fanciful and the similarity is certainly pure coincidence or the use of the word in a very limited community where Scots and Indians co-existed, however there was a surprising mutual liking between the Scots and the North American Indians.

Sporran

The need for such a 'purse' is self evident.

In the belted plaid, while the wearer could fashion various pockets from the upper portion of the fabric, they were small and not secure - valuable items such as money and lead balls for the musket & pistols, could easily be dislodged and lost. Originally the sporran was carried on the belt - just like a modern holidaymaker's money belt.

The 'working sporran' was usually very basic - a large circle of leather with holes punched around the periphery and then drawn together with a thin leather thong and attached to the belt.

For dressier occasions - usually the prerogative of the financially better-off - the sporran was much more ornate and hung at the front, either on the waist belt or on its own sporran belt.

A huge range of indulgent designs appeared with silver cantles and tassels.

Most were made of animal skins such as otter, badger, goat and seal and by the late 1800s there appeared the sporan molach or hair sporran usually made from goat skins and so large that it almost covered the front of the kilt.

Belts

A Highlander's leather belt was usually made of cowhide and was 80 to 100 mm wide with a brass or silver buckle. Some belts were reported as being highly decorated with silver ornaments intermixed with the leather like a chain.

If a Highlander was on a long trip and was short of food, he would tighten his belt which made his stomach feel less empty.

The better-off had even more ornate belts and sometimes the end that went through the buckle would be metal or silver that was highly engraved and decorated with fine stones or pieces of red corral.

The Sword Belt

The broad leather belt that lies across the chest was the sword belt - either of fairly plain design as shown on the left, or for more formal wear, in black patent leather with ornately ornamented buckles and keeps.

Hats

Many writings mention the Highlanders' bonnet - Boineid which came to be called the Tam’o’Shanter. This was knitted or made of cloth and was worn tight around the brow and very loose on top with a toorie for decoration - a bobble or pompom.

Tam o’Shanter

Harris tweed flat cap

Bonnets were mostly blue but were also made in brown and grey. In time it became smaller and was known as the Balmoral - boinead biorach which sometimes had a diced band (checked like a chess or draughts board) and the toorie on top.

Boinead biorach

Over the years, some wearers of the Balmoral wore it puffed up on the head and then creased it down the middle - producing a new style of hat called the Glengarry. By late Victorian times almost all the British Army wore this type of hat when they were in their working uniforms.

Balmoral

Piper Glengarry

Glengarry

Similar to a military overseas cap.

Worn two fingers above the right eye, cocked slightly to the right, with ribbons loose at the back.

Clan badge is affixed on the left-hand side, centered on the cockade.

Balmoral

Resembles a cross between a tam-o-shanter and a beret.

Worn straight on the head with the side pulled down over the right side.

Cockade should be worn over the left temple.

Ribbons can be worn loose or tied in a bow.

To achieve the correct shape, wet the bonnet in the shower, shape it with your hands, and let it dry on a Styrofoam wig manikin head.

Flat Cap

Traditional and typically done in a Harris tweed

The ribbons at the back were for adjusting the headband so that it fitted all head sizes. Tradition has it that in the army, Lowlanders let the ribbons hang free whilst Highlanders would tie them in a bow.

Feathers

It's not known exactly where the custom of Chiefs and Chietains wearing eagle feathers in their hat came from.

There is a strong suspicion however, that whilst the Scots did wear feathers in their hats at one time, the use and Chiefly significance of the eagle feathers may have been a Victorian invention based upon the American Indian tradition, however it is not known if the feathers were for embellishment or to denote rank.

Customs and the court of Lord Lyon declare that a feathers in a cap, either as a part of a metal broach or actual golden eagle feathers tucked into a balmoral decree certain status:

Four feathers = Monarch

Three feathers = Clan chief

Two feathers = Chieftain or Chief Younger

One feather = Armiger (those granted the right to bear personal arms)

Knives

The black knife - Sgian Dubh

The derivation of the name of this little 'weapon' is open to discussion. Traditionally the handle was made of black 'bog wood' - wood that had long lain submerged in a bog, and that's certainly an obvious origin (Black). Others point to the fact that originally it was a hidden knife and therefore rather sinister and used for 'black deeds.'

In rougher ages it was secreted in the oxter - the armpit - and could be withdrawn for use in a flash.

As violence and lawlessness disappeared, the need for such a hidden weapon diminished and it was then openly displayed, tucked into the hosetop.

“if one draws the Sgian Dubh one must draw blood”!

Dirk - Biodag

The Highland dirk grew directly from the early Ballock Knife - an old spelling of the more familiar and vulgar name for the male testes - which was prevalent throughout Western Europe in the Middle Ages.

In 1617 a Richard James describes Highlanders as wearing "a long kinde of dagger, broad in ye back and sharpe at ye pointe, which they call a darcke."

Ideal for close-quarter fighting, the dirk was a long stabbing weapon up to 50cm in length (20 inches).

Like the sgian dubh, when the need for its fighting role diminished, it often remained as part of formal Highland dress.

Affluent Highlanders would keep the dirk in a sheath often with one or more smaller knives or a knife and fork held by smaller sheathes. These were either mounted in tandem as shown or side by side.

After the 1745 uprising, many broadswords were cut down and made into dirks.

The dirk sheath would often be hung round the Highlander's waist or attached to a special dirk belt - the criosan biodag (pr: creeshan beedak).

That dirk belt became the standard kilt belt that we wear today.

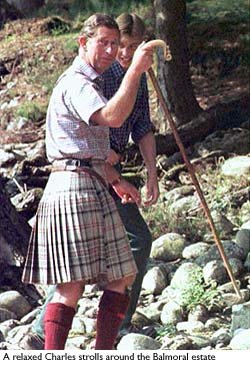

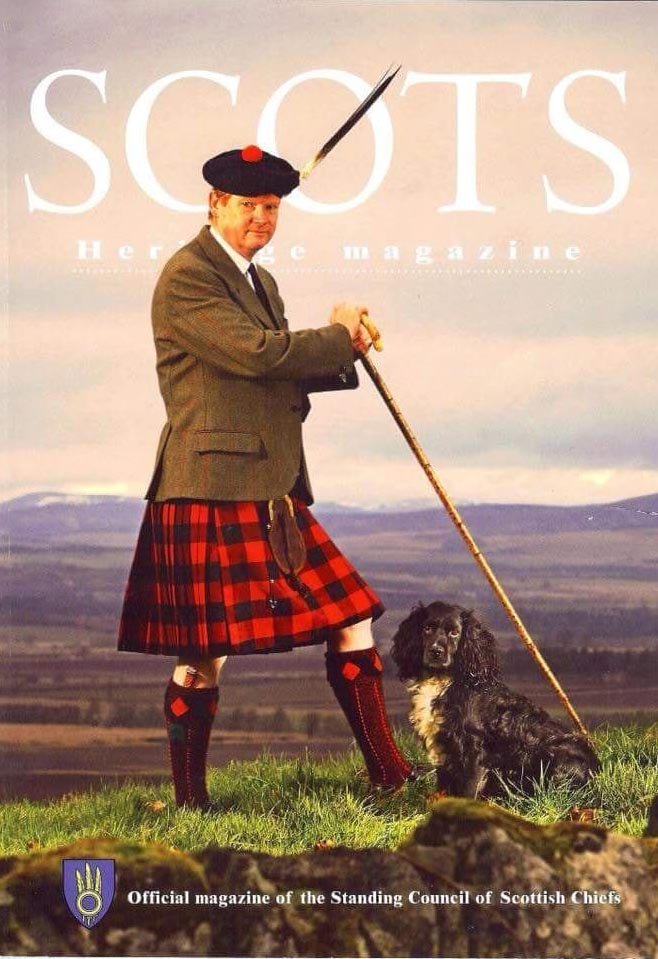

Walking sticks

In Scotland the tradition of going out with a walking stick has been around for centuries! Whether you are herding sheep, hiking an adventure trek or just a short walk. Scottish Walking Sticks are the perfect accessory for home or at your Highland games.

There are two basic types (of traditional, Scottish sticks): the shorter Kebbie and the longer Cromch

NOT TO BE CONFUSED WITH….

Staff Traditionally, a polearm / weapon. Watch a video on it here.

Mace Derived of medieval weapons, maces are very ceremonial (authority in parliaments and councils) and used by the Drum Major of a Highland band to direct or conduct the music. Watch a video of Mace flourishing

Kebbie, Bata (or Shillelagh in Irish)

A Kebbie is a rough Scottish walking stick, similar to an Irish shillelagh, but with a hooked head.

A Shillelagh is a specially weighted stick made from the knobby root end of Blackthorn. The knobby end is bored out and filled with either molten lead or molten silver, and allowed to harden.

Traditionally, a Shillelagh is 2/3ths the hight of it's owner. Scots were often too poor to afford swords so stick fighting was common and deadly, and became more common after Highland clearances (when none were allowed to bear arms).

Real Shillelaghs are hard to find. The best Shillelaghs are made from oak, ash or holly and spend a year buried in manure or a peat bog to temper the wood. After a year in manure or peat, they are rubbed in butter and left in a chimney to cure for a while, becomed blackened, and cure. They become as hard and unyielding as stone and are said only to break when their owner does.

Cromach

(pron. CROMach, with the ‘O’ as in song) from Scottish Gaelic, a noun that means a crooked or bent person, in the literal sense: a person who can't stand up straight.

A cromach is a shepherd’s crook, with a curved handle often carved from horn. Many are works of great craftsmanship. They are still used by shepherds but are also sometimes carried as a sort of informal baton of office by the high heid-yins (people in authority) at Highland Games, or just used by men out walking.

Traditionally the shape of the cromach head has a purpose: the curve of the head would be the right size for a sheeps neck making it easy for the shepard to control the sheep; and the little upturn could be used to hang a lantern. Most Scottish made cromachs are made of hazelwood or hawthorne for the staff; and a rams horn for the head. Some makers bend twigs on the tree and wait years for them to grow thick enough to cut for a cromach with the hook grown in.

The cromach gained popularity in the 20th century and has come into accepted use for the Stewards (or organizers) who run Highland Games (but use of the cromach is in no way limited to those in authority). The making of fine cromachs is a craft much admired in Scotland and they are generally made of hazel and sometimes with a horn handle with a carved finial.