Declaration of Arbroath

Sometimes referred to as the Scottish letter of Indpendance. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The 'Tyninghame' copy of the Declaration from 1320 AD

A letter, dated 6 April 1320

Written by Scottish barons; addressed to Pope John XXII.

It constituted King Robert I's response to his excommunication for disobeying the pope's demand in 1317 for a truce in the First War of Scottish Independence.

King Robert I popularly known as Robert the Bruce - was King of Scots from 1306 to his death in 1329

The letter asserted the antiquity of the independence of Scotland, denouncing English attempts to subjugate it.

Written in Arbroath Abbey by Bernard of Kilwinning, then Chancellor of Scotland and Abbot of Arbroath

Sealed by fifty-one magnates and nobles

The Declaration was intended to assert Scotland's status as an independent, sovereign state and defend Scotland's right to use military action when unjustly attacked.

The Declaration was part of a broader diplomatic campaign, which sought to assert Scotland's position as an independent kingdom, rather than its being a feudal land controlled by England's Norman kings, as well as lift the excommunication of Robert the Bruce. The pope had recognised Edward I of England's claim to overlordship of Scotland in 1305 and Bruce was excommunicated by the Pope for murdering John Comyn before the altar at Greyfriars Church in Dumfries in 1306. This excommunication was lifted in 1308; subsequently the pope threatened Robert with excommunication again if Avignon's demands in 1317 for peace with England were ignored. Warfare continued, and in 1320 John XXII again excommunicated Robert I. In reply, the Declaration was composed and signed and, in response, the papacy rescinded King Robert Bruce's excommunication and thereafter addressed him using his royal title.

Context

The wars of Scottish independence began as a result of the deaths of King Alexander III of Scotland in 1286 and his heir the "Maid of Norway" in 1290, which left the throne of Scotland vacant and the subsequent succession crisis of 1290-1296 ignited a struggle among the Competitors for the Crown of Scotland, chiefly between the House of Comyn, the House of Balliol, and the House of Bruce who all claimed the crown. After July 1296's deposition of King John Balliol by Edward of England and then February 1306's killing of John Comyn III, Robert Bruce's rivals to the throne of Scotland were gone, and Robert was crowned king at Scone that year. Edward I, the "Hammer of Scots", died in 1307; his son and successor Edward II did not renew his father's campaigns in Scotland. In 1309 a parliament held at St Andrews acknowledged Robert's right to rule, received emissaries from the Kingdom of France recognising the Bruce's title, and proclaimed the independence of the kingdom from England.

By 1314 only Edinburgh, Berwick-upon-Tweed, Roxburgh, and Stirling remained in English hands. In June 1314 the Battle of Bannockburn had secured Robert Bruce's position as King of Scots; Stirling, the Central Belt, and much of Lothian came under Robert's control while the defeated Edward II's power on escaping to England via Berwick weakened under the sway of his cousin Henry, Earl of Lancaster.

King Robert was thus able to consolidate his power, and sent his brother Edward Bruce to claim the Kingdom of Ireland in 1315 with an army landed in Ulster the previous year with the help of Gaelic lords from the Isles. Edward Bruce died in 1318 without achieving success, but the Scots campaigns in Ireland and in northern England were intended to press for the recognition of Robert's crown by King Edward. At the same time, it undermined the House of Plantagenet's claims to overlordship of the British Isles and halted the Plantagenets' effort to absorb Scotland as had been done in Ireland and Wales. Thus were the Scots nobles confident in their letters to Pope John of the distinct and independent nature of Scotland's kingdom; the Declaration of Arbroath was one such.

Content

The text makes claims about the ancient history of Scotland and especially the Scoti, forbears of the Scots, who the Declaration claims originated in Scythia Major and migrated via Spain to Britain, dating their migration to "1,200 years from the Israelite people's crossing of the Red Sea".

The Declaration describes how the Scots had "thrown out the Britons and completely destroyed the Picts", resisted the invasions of "the Norse, the Danes and the English", and "held itself ever since, free from all slavery".

It then claims that in the Kingdom of Scotland, "one hundred and thirteen kings have reigned of their own Blood Royal, without interruption by foreigners".

The text compares Robert Bruce with the Biblical warriors Judah Maccabee and Joshua.

The Declaration made a number of points:

that Edward I of England had unjustly attacked Scotland and perpetrated atrocities;

that Robert the Bruce had delivered the Scottish nation from this peril; and,

most controversially, that the independence of Scotland was the prerogative of the Scottish people, rather than the King of Scots.

The Pope heeded the arguments contained in the Declaration, influenced by the offer of support from the Scots for his long-desired crusade if they no longer had to fear English invasion. He exhorted Edward II in a letter to make peace with the Scots.

However, it did not lead to his recognising Robert as King of Scots, and the following year was again persuaded by the English to take their side and issued six bulls to that effect.

Eight years later, on 1 March 1328, the new English king, Edward III, signed a peace treaty between Scotland and England, the Treaty of Edinburgh–Northampton. In this treaty, which was in effect for until 1333, Edward renounced all English claims to Scotland. In October 1328, the interdict on Scotland, and the excommunication of its king, were removed by the Pope.

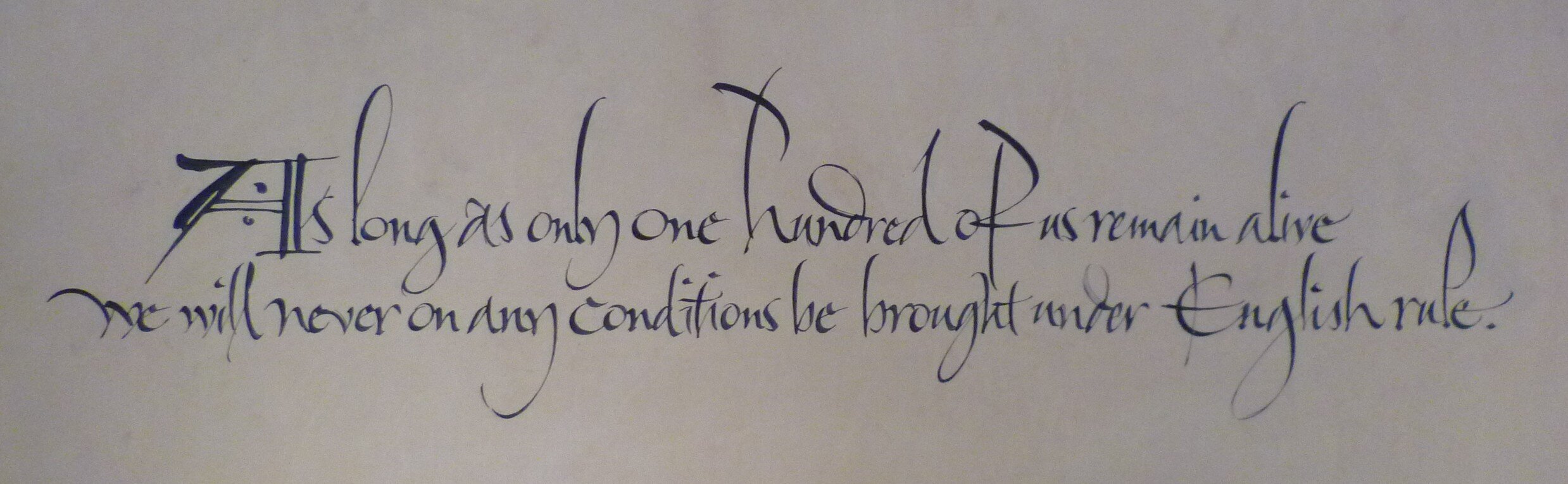

The most-cited passages of the Declaration, translated from the Latin original as displayed on the walls of the National Museum of Scotland.

Signatories

There are 39 names—eight earls and thirty-one barons—at the start of the document, all of whom may have had their seals appended, probably over the space of some time, possibly weeks, with nobles sending in their seals to be used.

The letter itself is written in Latin. It uses the Latin versions of the signatories' titles, and in some cases, the spelling of names has changed over the years. This list generally uses the titles of the signatories' Wikipedia biographies.

Duncan, Earl of Fife (changed sides in 1332)

Thomas Randolph, Earl of Moray (nephew and supporter of King Robert although briefly fought for the English after being captured by them, Guarian of the Realm after Robert the Bruce's death)

Patrick Dunbar, Earl of March (or Earl of Dunbar) (changed sides several times)

Malise, Earl of Strathearn (King Robert loyalist)

Malcolm, Earl of Lennox (King Robert loyalist)

William, Earl of Ross (earlier betrayed King Robert's female relatives to the English)

Magnús Jónsson, Earl of Orkney

William de Moravia, Earl of Sutherland

Walter, High Steward of Scotland (King Robert loyalist)

William de Soules, Lord of Liddesdale and Butler of Scotland (later imprisoned for plotting against the King)

Sir James Douglas, Lord of Douglas (one of King Robert's leading loyalists)

Roger de Mowbray, Lord of Barnbougle and Dalmeny (later imprisoned for plotting against King Robert)

David, Lord of Brechin (later executed for plotting against King Robert)

David de Graham of Kincardine

Ingram de Umfraville (fought on the English side at Bannockburn but then changed sides to support King Robert)

John de Menteith, guardian of the earldom of Menteith (earlier betrayed William Wallace to the English) = Grandfather-in-Law of Sir Maurice Buchanan, 10th of Buchanan

Alexander Fraser of Touchfraser and Cowie

Gilbert de la Hay, Constable of Scotland (King Robert loyalist)

Robert Keith, Marischal of Scotland (King Robert loyalist)

Henry St Clair of Rosslyn

John de Graham, Lord of Dalkeith, Abercorn & Eskdale

David Lindsay of Crawford

William Oliphant, Lord of Aberdalgie and Dupplin (briefly fought for the English)

Patrick de Graham of Lovat

John de Fenton, Lord of Baikie and Beaufort

William de Abernethy of Saltoun

David Wemyss of Wemyss

William Mushet

Fergus of Ardrossan

Eustace Maxwell of Caerlaverock

William Ramsay

William de Monte Alto, Lord of Ferne

Alan Murray

Donald Campbell

John Cameron

Reginald le Chen, Lord of Inverugie and Duffus

Alexander Seton

Andrew de Leslie

Alexander Straiton

In addition, the names of the following do not appear in the document's text, but their names are written on seal tags and their seals are present:[21]

Alexander de Lamberton (became a supporter of Edward Balliol after the Battle of Dupplin Moor, 1332)

Edward Keith (subsequently Marischal of Scotland; d. 1346)

Arthur Campbell (Bruce loyalist)

Thomas de Menzies (Bruce loyalist)

John de Inchmartin (became a supporter of Edward Balliol after the Battle of Dupplin Moor, 1332; d. after 1334)

John Duraunt

Thomas de Morham

The Abbey of of Arbroath

Arbroath Village lies north of Dundee in the province of Angus and the site was chosen by King William the Lion to provide an Abbey for a group of Tironensian Benedictine monks from Kelso Abbey. The Abbey was consecrated in 1197 with a dedication to the deceased Saint Thomas Beckett whom the king had met at the English court. The last Abbott was Cardinal David Beaton who in 1522 succeeded his uncle James who became Archbishop of St. Andrews.

King William gave the Abbey independence from its founding Abbey, Kelso Abbey, and endowed it generously, including income from 24 parishes, land in every royal burgh. The Abbey’s monks were allowed to run a market and build a harbour. King John of England gave the Abbey permission to buy and sell goods anywhere in England (except London) toll free. The Abbey became the richest in Scotland and is famous for its links to the 1320 Declaration of Scottish Independence.

The Abbey was built over some sixty years using the local red standstone. The architectural style is mainly Early English – though the round arched work is akin to early Norman. The triforium ( open arcade ) above the door, is unique in Scottish medieval architecture. The cruciform church measured 84m long by 49m wide. Little remains of the claustral buildings except for the impressive gateway. The Abbot’s House, a building of the 13th, 15th, and 16th centuries is the best preserved of its type in Scotland.

The Abbey fell into ruin after the Reformation and from around 1520 the Abbey stones were raided to construct buildings in the village of Arbroath – this act continued until 1815 when the authorities forbade further destruction of this historic building.

On Christmas day 1950, the Stone of Destiny upon which Scottish Kings were crowned disappeared from Westminister Abbey. On April 11, 1951 the missing stone was found lying on the site of Arboroath Abbey’s altar.

In 1947 a major historical re-enactment commemorating the Declarations signing was held within the roofless remains of the Abbey Church. The celebration is run by the local Arbroath Abbey Pageant Society, This is not an annual event, however, a special event to mark the signing is held every year on the 6th of April and involves a street procession.

In 2001 a visitors centre was opened to the public.