The Stone of Scone

Replica of the Stone of Scone, Scone Palace, Scotland. Photo by Aaron Bradley from Vancouver, Canada, via Wikipedia

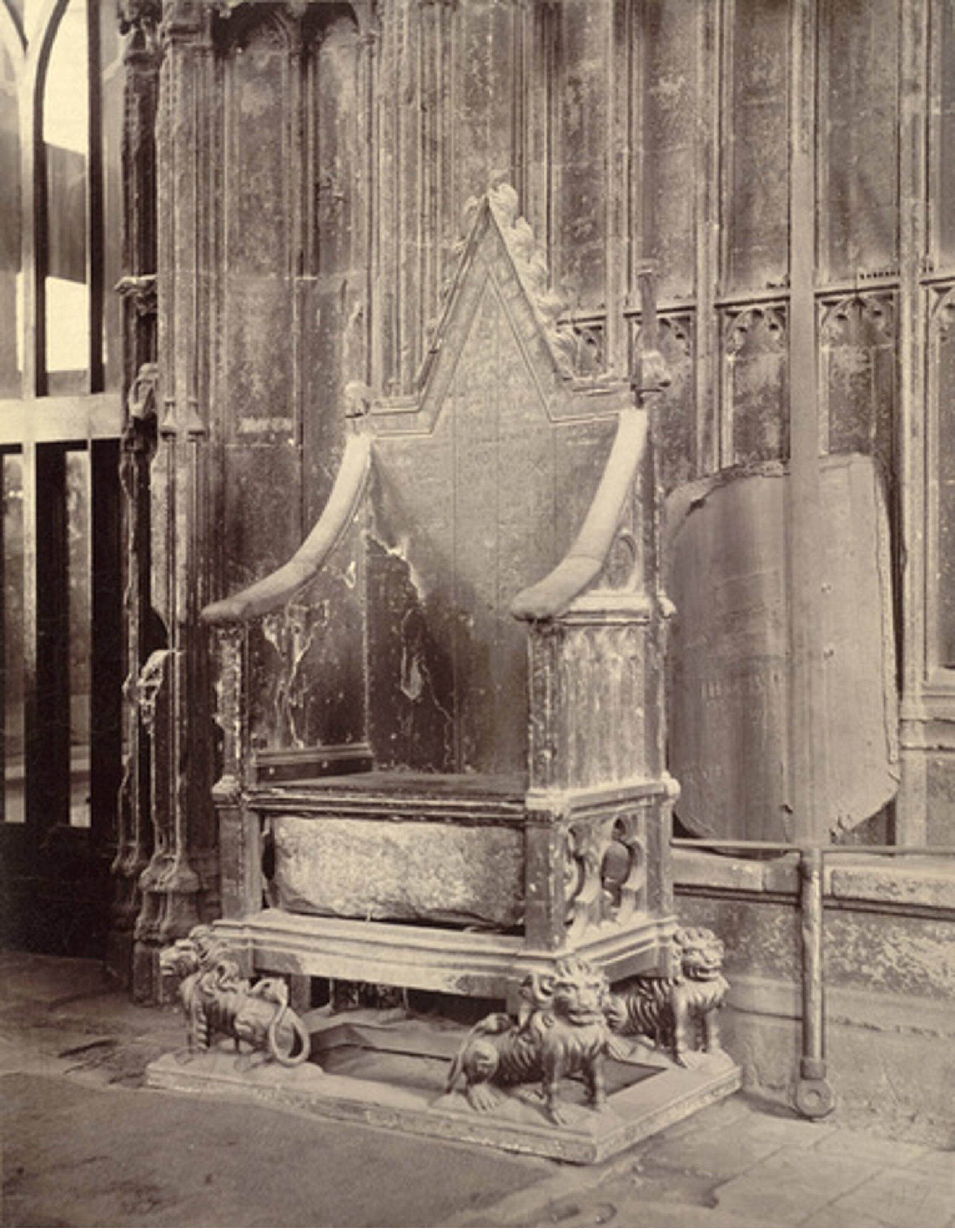

The Stone of Scone (An Lia Fáil), - also known as the Stone of Destiny, and often referred to in England as The Coronation Stone is an ancient symbol of Scottish sovereignty. For centuries it has played a key role in the coronations of Scottish and British monarchs.

It is an oblong block of red sandstone that has been used for centuries in the coronation of the Monarchs of Scotland and is also known as Clach-na-cinneamhain in Scottish Gaelic.

Historically, the Stone was kept at the now-ruined Scone Abbey in Scone, near Perth, Scotland, having been brought there from Iona in 841 AD.

IONA

SCONE

According to legend, the sandstone slab was used by the biblical figure Jacob as a pillow when he dreamed of a ladder reaching to heaven and then brought to Scotland by way of Egypt, Spain and Ireland.

The rock, also known as the Stone of Destiny, was used for centuries in the coronation ceremonies of Scottish monarchs.

Following his victory at the Battle of Dunbar in 1296, England’s King Edward I (Longshanks) seized the Stone of Scone and had it fitted into the base of a specially crafted wooden Coronation Chair on which English—and later British—monarchs have been crowned inside London’s Westminster Abbey ever since.

At the time, the Stone was viewed as a symbol of Scottish nationhood, so by removing the Stone to London, Edward I was declaring himself 'King of the Scots', and subsequently used in the coronation of the monarchs of England, then Great Britain and was last used in 1953 for the coronation of Elizabeth 11.

The Theiving Return

In December 1950, a few days before Christmas, four students from Glasgow (Ian Hamilton, Gavin Vernon Kay Matheson and Alan Stuart), drove to London. The plan was funded by Glasgow businessman, Robert Gray, under the belief that removing the Stone the group would promote the cause for Scottish devolution and reawaken a national identity amongst the Scottish people.

On arrival in London they decided to make an immediate attempt at removing the Stone from the Abbey, but were thwarted when Ian Hamilton was caught by a nightwatchman after the Abbey doors had been closed. He was briefly questioned, and then let go.

The following day Vernon and Stuart returned to Westminster Abbey in the middle of the night, gaining entrance through Poets Corner.

Reaching the Chapel containing the tomb of Edward1 and King Edwards Chair they pulled down the barrier, removing the Stone from under the Chair.

However, it crashed to the floor and broke into two pieces. They dragged the larger piece down the high altar steps, then took the smaller piece to one of the cars waiting outside.

As he did this, Kay Matheson noticed a policeman in the gaslight so Hamilton and Matheson immediately fell into a lovers' clinch. The policeman stopped and the three proceeded to converse, even though it was 5am. Having shared some jokes and a cigarette, Matheson and Hamilton drove off.

The stone was so heavy that the springs on the car were sagging, so fearing the alarm had been raised, they hid the large pieces of stone and made their way back to Scotland.

On discovering that the Stone was missing, the authorities closed the border between Scotland and England for the first time in four hundred years.

A fortnight later, the two pieces were recovered and brought to Glasgow where they hired a stonemason to mend the Stone and placed a brass rod inside the Stone containing a piece of paper. To this day, nobody knows what was written on the piece of paper.

In April 1951 the police received a message and the repaired stone was discovered draped in a Scottish national flag on the high altar of the ruined Arbroath Abbey where, in 1320, the assertion of Scottish nationhood was made in the Declaration of Arbroath.

No charges were ever brought against the students, and the stone was returned to Westminster Abbey.

The Stone was returned to Westminster Abbey in February 1952 and the police conducted an investigation with a focus on Scotland.

All four of the group were interviewed and all but Ian Hamilton later confessed to their involvement, however the authorities decided not to prosecute as the potential for the event to become politicised was far too great.

Sir Hartley Shawcross, addressing Parliament on the matter, said: "The clandestine removal of the Stone from Westminster Abbey, and the manifest disregard for the sanctity of the abbey, were vulgar acts of vandalism which have caused great distress and offence both in England and Scotland. I do not think, however, that the public interest required criminal proceedings to be taken”.

The raid was completely unexpected and gave the cause of Scottish devolution and nationalism a brief sense of prominence in the public conscience throughout the country.

The students became notorious for the daring heist and in Scotland they became immensely popular. Ultimately, the heist and the students became synonymous with the devolution and nationalist political movements in Scotland from 1950 onwards.

Years after the infamous theft, Ian Hamilton said: “When I lifted the Stone in Westminster Abbey, I felt Scotland’s soul was in my hands.”

Over time, the incident encouraged a belief in change, throwing open to scrutiny the Union, which had existed since 1707.

Long before the Stone was officially returned to Scotland in 1996 and the Scottish people voted for devolution in 1997, there is no doubt the removal of the Stone of Scone in 1950 contributed to those events.

Formal Return

Seven hundred years after King Edward I removed the Stone of Scone from Scottish soil, British Prime Minister John Major unexpectedly announced its return, which occurred on November 15, 1996, to reside in Edinburgh Castle but it will be made available for future coronation ceremonies at Westminster Abbey.

Rumours still persist in Scotland, that the rock taken by King Edward I was a replica and that the monks at Scone Abbey hid the actual stone in a river or buried it for safekeeping.

The removal of the stone was the subject of a contemporary Scottish Gaelic song by Donald MacIntyre, “Oran na Cloiche” ("The Song of the Stone") and its return to London was the subject of an accompanying lament, "Nuair a Chaidh a' Chlach a Thilleadh" ("When the Stone Was Returned").

In 2008, Hamilton's book, The Taking of the Stone of Destiny, was made into a film entitled Stone of Destiny, depicting Hamilton (played by Charlie Cox as the protagonist leading a team of students to reclaim the Stone of Scone.

A new analysis of the stone is offering researchers insights on its origins

Story from The Smithstonian, by Teresa Nowakowski

Experts at Historic Environment Scotland (HES) used cutting-edge scanning tools to create a 3D model of the stone. They also conducted an X-ray fluorescence analysis that revealed the object’s elemental composition.

Key findings include

previously unseen markings that could be Roman numerals,

traces of copper alloy and gypsum plaster,

tool marks left during both the stone’s original carving and a 1951 repair.

“The discovery of previously unrecorded markings is … significant, and while at this point we’re unable to say for certain what their purpose or meaning might be, they offer the exciting opportunity for further areas of study,” says Ewan Hyslop, head of research and climate change at HES, in a statement. “We may not have all the answers at this stage, but what we’ve been able to uncover is testament to a variety of uses in the stone’s long history and contributes to its provenance and authenticity.”

Ewan Campbell, an archaeologist at the University of Glasgow who was not involved in the research, tells Live Science’s Owen Jarus that he finds the presence of a copper alloy on the stone “more important” than the discovery of the unidentified markings. The remnants of copper, Campbell adds, suggest “some object, possibly a relic such as a saint’s bell, was positioned on the stone for a long period.” Ewan suggests that the markings are probably “crude crosses,” not numerals.

But the scientific analysis quells rumors that Scottish nationalists replaced the stone with a replica during the 1950 heist.

The research project also allowed experts to take a closer look at tooling marks on the stone, which confirmed it was “roughly worked by more than one stonemason with a number of different tools, as was previously thought,” says Hyslop in the statement.

Roman numerals or crude crosses? Click to enlarge